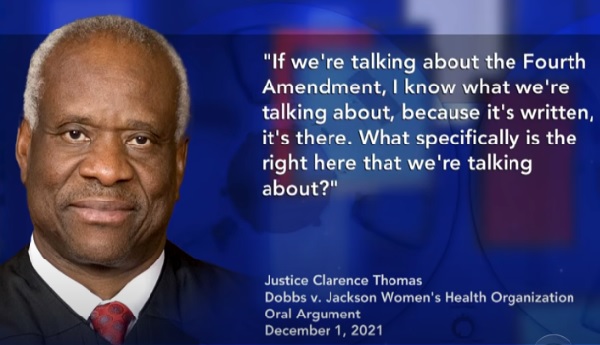

Last week I was watching the opening monologue of The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, where in discussing Dobbs v Jackson Women's Health Organisation which has the potential to overturn the precedent set by Roe vs Wade that women in the United States have a right to get an abortion of a pregnancy, Mr Colbert made sport of the following comment:

One of the enduring features of comedy and especially satire, is to take exactly what your opponent has said and place that statement in a new light in order to either make a parody of itself, or to shine a light on the apparent internal logic failure or otherwise stupidity of the speaker. In selecting this particular quote, Mr Colbert painted Justice Clarence Thomas as a dunderhead and went on his merry comedic way. All of that is completely valid in the art of comedy and satire.

However, if you are trying to use a satirical comedy show as a source of news, you had best check yourself before you wreck yourself on the shore of misinformation. Comedy and satire can speak truths but they aren't inherently the best source of truthiness. If you place Justice Clarence Thomas' statement back into the stream of discussion, what you find is that he is in fact asking a very serious question:

https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/2021/19-1392_4425.pdf

JUSTICE THOMAS: General, would you specifically tell me -- specifically state what the right is? Is it specifically abortion? Is it liberty? Is it autonomy? Is it privacy?

GENERAL PRELOGAR: The right is grounded in the liberty component of the Fourteenth Amendment, Justice Thomas, but I think that it promotes interest in autonomy, bodily integrity, liberty, and equality. And I do think that it is specifically the right to abortion here, the right of a woman to be able to control, without the state forcing her to continue a pregnancy, whether to carry that baby to term.

JUSTICE THOMAS: I understand we're talking about abortion here, but what is confusing is that we -- if we were talking about the Second Amendment, I know exactly what we're talking about. If we're talking about the Fourth Amendment, I know what we're talking about because it's written. It's there. What specifically is the right here that we're talking about?

GENERAL PRELOGAR: Well, Justice

Thomas, I think that the Court in those other

contexts with respect to those other amendments has had to articulate what the text means and the bounds of the constitutional guarantees, and it's done so through a variety of different tests that implement First Amendment rights, Second Amendment rights, Fourth Amendment rights. So I don't think that there is anything unprecedented or anomalous about the right that the Court articulated in Roe and Casey and the way that it implemented that right by defining the scope of the liberty interest by reference to viability and providing that that is the moment when the balance of interests tips and when the state can act to prohibit a woman from -- from getting an abortion based on its interest in protecting the fetal life at that point.

JUSTICE THOMAS: So the right specifically is abortion?

GENERAL PRELOGAR: It's the right of a woman prior to viability to control whether to continue with the pregnancy, yes.

JUSTICE THOMAS: Thank you.

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, SCOTUS, 1st Dec 2021

In context, Justice Clarence Thomas is doing two things: firstly he is asking the claimants in the case to specifically define what it is that they are asking for because the Supreme Court which has the power to emphatically say what the law is, wants to make sure that the judgement will actually fit the terms and scope of the subject that the claimant is asking about and secondly, he is actually asking the claimant to be more precise about the claim, so that the work of the court in this decision is as limited as possible. In a rights case, although the Supreme Court has very large, sweeping, and wide ranging powers, it is also aware that is possesses the power of original jurisdiction and so by creating or denying a right, it wants to limit the terms of its decision as narrowly as possible, lest it start to interfere with other rights issues and even the operation of other law itself.

In other words, by probing and asking and questioning for the claimants to be very specific about what they are asking the court to do, Justice Clarence Thomas is being quite deliberate about dispensing the power that the court has. Rather than being a dunderhead, Justice Thomas is trying to be precise in an area of law which is very very blunt.

Immediately we run into the obvious problem that I think that the whole area of giving the court the ability to determine rights are, is. Suppose that I was on the court. I personally think that in general that there shouldn't be a right to abortion in most except on grounds that it is likely to endanger the life of the mother and in examples of rape et cetera. Immediately you're likely to think that my opinion is either noble or monstrous.

In general I do not like the right to bear arms, or have an abortion, or the right to die through euthanasia because I see that the right to life of someone is very likely to be impinged and someone's life is destroyed through the actions of someone else. Especially with the right to abortion if it exists, then at some point you have to declare someone as an unperson and to be honest, as I have no idea where that point actually is (due to the paradox of the pile of beans), then I err on the side that I and in fact nobody else is qualified to make such a decision sensibly. I think that abortions should be safe and exceedingly rare but not generally legal.

Before you declare me to be a monster, remember, that I come from an equally vexing and challenging place where different people's rights are competing with each other (namely the mother and child). That takes you to a very very long thought process which looks at a whole range of issues such as bodily autonomy, vulnerability, responsibility issues and what not and more than likely, we will arrive at different conclusions. I am also informed by faith as well as other documents like the Declaration of the Rights of The Child, which you are free to accept or reject.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

Bearing in mind that, as indicated in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, "the child, by reason of his physical and mental immaturity, needs special safeguards and care, including appropriate legal protection, before as well as after birth",

- Preamble, UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20th Nov 1989

Let's assume that you disagree with me and think that my opinion is monstrous (I think that's a fair assumption for a lot of people). Do you want me to be in charge of making such a decision? I would wager, no. Actually, I would wager that quiet vehemently "no" and you will even go so far as to spit in my face to make the point. If "no", then I should really be in charge of making a rights decision like this? If not me, then I will immediately ask, on what basis should a court of 9 be allowed to make such a decision?

The method of selecting those 9 people is by the nomination of the President (which is a political position) which is then agreed to or not agreed to with the advice and consent of the Senate (which is made up of 50 political positions). Is that sensible? Should the ability to make and decide what rights exist, be given over to an entirely political process?

I will argue that every right, which is the ability to do something at law or the privilege of having something recognised at law or a benefit conferred on someone by the law, is always going to be a political process and second to that, I absolutely hate the idea of a Bill of Rights.

The United States ran into this problem at the outset, and in fact, Thomas Jefferson who famously wrote the Declaration of Independence, expressed his grave concern about including a Bill of Rights in the Constitution to James Madison. It is Madison and Hamilton who are mostly responsible for laying out the three-ring circus that is the United States Constitution and I think that they actually did an awful job. Not only do I think that the instrument of government by which the United States is awful but I think that history has proven me right by virtue of the fact that it has been copied by exactly zero other countries.

Jefferson had this to say:

https://jeffersonpapers.princeton.edu/selected-documents/thomas-jefferson-james-madison

Every constitution then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years. If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right.—It may be said that the succeeding generation exercising in fact the power of repeal, this leaves them as free as if the constitution or law had been expressly limited to 19 years only.

- Thomas Jefferson, to James Madison, 6th Sep 1789

Again in context, Jefferson argues that rights, whatever they happen to be, should be the domain of the living rather than being a tombstone of the dead, around which the living are tied to via a rope around the neck. Thomas Jefferson couldn't have foreseen the right to health care, the right to education, the right to reasonable terms of employment and working conditions, and given that he lived in an almost pre-industrial and very much agricultural nation, then the right to abortion wouldn't have even been imagined. Also, the country which he was writing in, was in part predicated by rich people agitating the general public for the right to keep and retain slaves. The United States was literally started because of a demand for the right to vote (No Taxation Without Representation) but where the Coercive/Intolerable/Punitive Acts were in part motivated by the colonies' bucking on the subject of slavery (see Somerset's Case (1772), and later Knight v Wedderburn (1777)).

If I shouldn't be allowed to decide what rights exist, and presumably a political process shouldn't be allowed to decide what rights exist, and parliaments shouldn't be allowed to decide what rights exist, then I ask upon what basis does anyone think that a Bill Of Rights is a good idea?

Like Jefferson (who by the way owned and kept slaves and more than likely had an affair with one whilst in the office of the President), I hate the idea of a Bill Of Rights for the same reason. I very much think that some rights can and will exist through a process of discovery (such as the right to live in a clean and viable environment) and that some rights which used to exist in the past are absolutely not appropriate for today (such as the right to bear arms). I hate the idea that rights should become crystallised and never ever subject to review.

I agree with Jefferson that rights should belong to the land of the living and to that end, the only sensible and permanent right which anyone will logically agree upon is the right to free speech but even that should come with limits surrounding defamation, racism, sedition, incitement and the harm that it is likely to do to others if exercised. The 1st Amendment to the Constitution gives me the right to tell you that the 2nd Amendment is horrible and that the only amendment that I actually like is the 10th Amendment.

The problem with writing fixed rights into a constitution is that as a constitution is the set of rules by which other laws are made, the safeguards which are invariably written into a constitution makes it difficult to remove or expand rights. If you carve a set of rules into a very big rock, then convincing anyone to carve new rules into the rock is difficult. Convincing anyone to deface the rock is difficult. Getting enough people to use their efforts to move the rock, especially when other people want to push it in the other direction is difficult.

In my country of Australia, the framers of our Constitution, also faced this dilemma and deliberately did not include a Bill Of Rights for this very same reason. Had they done so, then Australia might very well be in a similar predicament to the United States, where no right to health care and/or education exists because there are people who prefer that not to be the case.

Jefferson and Hamilton both came to this conclusion and the only reason why the United States has a Bill Of Rights, is not because of the imagined wisdom of the forefathers but because the people who were arguing in sweaty basements (and who were all men) were arguing on behalf of their own little state who were in very real danger of being swamped in a wave of Federalism. The United States might very well tell itself that it was conceived in liberty but when it came time to write the rules which determine how you write rules, it was carried in a spirit of knavery and wingnuttery. I imagine that there were lots and lots of cuss words thrown about and that hatred and enmity ran hot - remember: the Vice-President shot and killed the former Secretary to the Treasury in a duel; using the very power conferred to him via the 2nd Amendment.

From the outset, Thomas Jefferson, who by the way wrote that he held certain truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal but proved that he thought that this was a lie by owning other people as chattel goods, conceded that the constitution should be a contestable document. Already within his lifetime the right to own other people or not to be owned as chattel goods was being contested and by demonstration, it took a lot of other people to die before his entire generation got out of the way. It took the bloodiest war that the United States has ever fought, to finally settle the matter.

All of this generally goes on to show that rights, where they do exist, belong to the domain of the living and that as society changes and decides for itself what rights to confer upon itself (and what rights are no longer appropriate), that the idea of a fixed Bill of Rights as handed down by forefathers with imagined god-like status, is monumentally stupid. There should be no final victory and no final defeat and no final statement on what rights do and do not exist.

So now what? In my perfect world (and having successfully infuriated everyone across the authoritarian/progressive political spectrum) rights should always be up for debate. I know that I am so incompetent to be able to decide most of these issues that I should not be given the power to do so. I would submit therefore, that every member in society generally, who has probably thought about issues like this, to a degree less than I have, is also as equally incompetent as I and should also not generally be trusted in making a decision such as this. The problem is that because each of us are selfish individuals who shouldn't be given the power to make and confer rights or destroy and remove, we live inside a paradox where someone at some point is forced to by virtue of their job to do so. Say what you like about Justice Clarence Thomas, I think that in cases like this that people like him have a truly awful job and I certainly wouldn't want to do it.